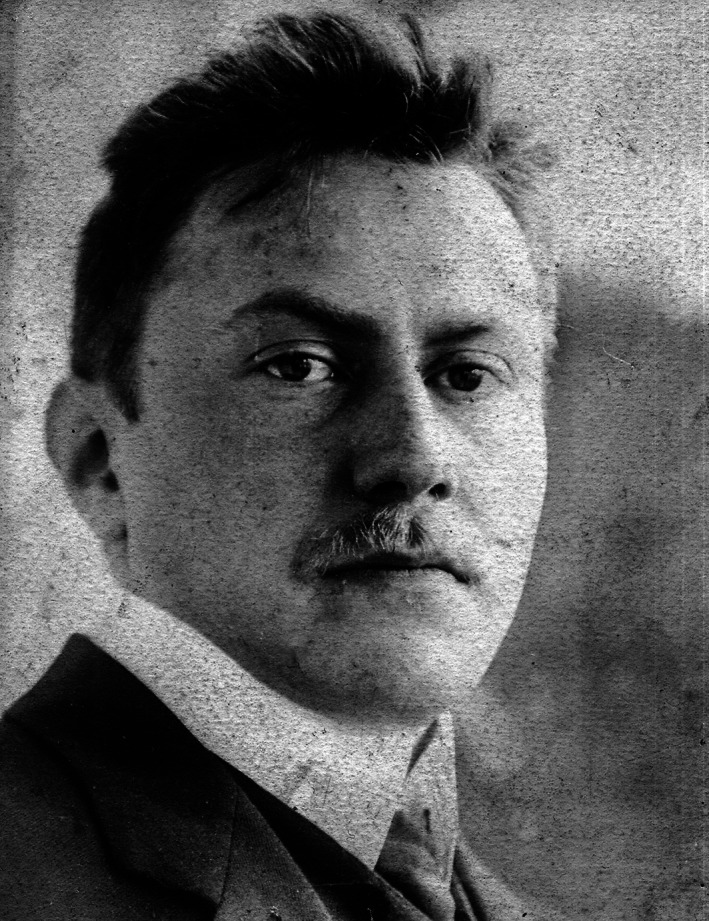

Ludwik Hirszfeld survived the Holocaust and made multiple discoveries about blood

One of the pioneers of blood group science and blood transfusion was Ludwik Hirszfeld, a Polish physician, immunologist, and microbiologist born in 1884. Hirszfeld was Jewish and survived the Holocaust in Eastern Europe and even helped people through medicine in the Warsaw Ghetto.

Hirszfeld is credited with helping discover and coin the different ABO blood types, finding out along with scientist Emil von Dungern that human blood types are inheritable, and discovering blood group frequency differences between populations with his wife, scientist Hanna Hirszfeld. He made fundamental discoveries and contributions in immunogenetics and immunohematology.

Discoveries during the First World War

Through both world wars, Hirszfeld’s commitment to science and medicine helped many people to survive typhus and typhoid fever epidemics. He served as a Serbian Army doctor in World War I and made important scientific findings about strains of typhoid. His introduction of mass disinfection helped slow the spread of the epidemic.

With his wife, he acquired blood samples from thousands of soldiers of different races and ethnicities during World War I and used the information they collected about blood types as a basis for theories that blood types are tied to different geographical locations and ethnicities that originated with one “pure blood type.” These false theories were later adopted and transformed into the basis for a “superior race” and eugenics in Nazi Germany.

After the war, Hirszfeld helped create the National Institute of Hygiene in Warsaw and developed blood transfusion centers in Poland.

Helping others during the Holocaust

During World War II, Hirszfeld was sent to the Warsaw Ghetto, where he helped organize secret medical courses and led the way in containing the typhus epidemic that plagued the ghetto. He designed a simple test to detect typhoid bacteria in urine and secretly vaccinated people against the disease. Hirszfeld taught more than 500 students about bacteriology and more, but only 50 of those students survived the war.

He detailed the horrors of overcrowding, starvation, and non-existent healthcare in the ghetto in his book, “The Story of One Life.” He and Hanna escaped the ghetto in 1941.

Continued blood science discoveries

Hirszfeld’s research continued after the war, with one of his greatest findings at that time being the theory of serological conflict between mother and fetus, which addresses hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn that is caused by incompatibility of the Rh antigen. He introduced exchange transfusions, which saved nearly 200 children at the time.

He co-authored 395 scientific papers in his lifetime, and more than half of them were about blood science and transfusion.

To learn more about blood donation, visit SouthTexasBlood.org.